At just over a half a pound in weight, chick #9 was one of the smallest translocated Laysan Albatross chicks we had ever brought in- most birds weigh 1-2 pounds by the time we receive them at three weeks old, but she was less than half of that. Initially, we thought her low weight was because she was slightly younger than the other chicks, but as the weeks wore on, we realized something else was happening; she was not getting bigger. The belly of a young albatross chick feels like a water balloon- squishy and full of their diet of fish oil. In contrast number 9’s belly felt spongy. And then there was her breath…. Albatross breath on a good day smells pretty awful, but it is a ‘clean fish’ smell rather than a ‘sour fish’ smell; when we smell ‘sour fish’ we typically know something is wrong. But taking a wild bird to a vet with nothing more to describe her symptoms than ‘spongy’ and ‘smelly’ doesn’t make it easy to diagnose a problem. Those two symptoms combined with her lack of weight gain led us to suspect that there was something blocking her digestive system and preventing her from digesting her food and that the undigested food was causing her breath to smell.

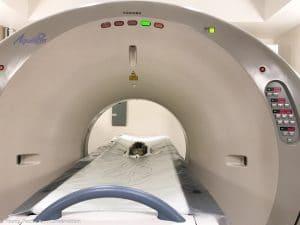

We were referred to Dr. Lam, an avian surgery specialist at VCA specialty clinic in Pearl City, to assist with the diagnosis. He recommended an ultrasound (since it would not require us to anesthetize her) to get an initial diagnosis. While it’s hard to see in the picture below, the ultrasound indicated there were several hard objects stuck in her stomach.

An ultrasound photograph showing plastic inside a Laysan Albatross chick

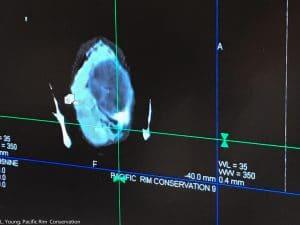

The hard part was trying to locate where and what was stuck before proceeding to surgery. So #9 was put under general anesthesia and given a CT scan to further refine the diagnosis. Watching a tiny albatross chicks get a CT scan was a stark juxtoposition of the natural world we work in, and the tools we sometimes use to do our work! The CT scan revealed a blockage of mineral-like deposits (minerals appear bright and shiny on CT scans) in the opening between her proventriculus and ventriulus (similar to our small and large intestines), but it was hard to determine what it was. Had she swallowed a rock? Was it sand? We couldn’t tell. The CT scan had also picked up several plastic objects further down her digestive tract. Regardless of what it was, it was going to require surgery to remove, or number nine would slowly starve to death.

Left: Laysan Albatross chick getting a CT scan Right: CT scan- bright spot shows minerals

The options presented to us were an endoscopy or exploratory surgery. An endoscopy is where a small camera is inserted down the birds throat (while they are under anesthesia) to visualize the blockage, and then if it’s small enough, it may be able to be removed with a tiny pair of forceps. Since #9 was so small, we chose to attempt an endoscopy over general surgery. We were thankfully allowed to be present during the procedure, and were able to witness the amazing skill of Dr. Lam and his team. It was immediately clear that the blockage causing the issue was compacted sand in the narrow opening between her proventriculus and ventriculus. With several bursts of water, the sand clump dissolved revealing that several plastic items had been lodged in with it, and likely caused the sand to clump and form the blockage. Over a harrowing 30 minute period, a small 1cm piece of white plastic was removed, and several small pieces of a red balloon came out as her heart rate raced up and down. Compared to what an albatross chick will normally cough up, all of these were very small pieces, but when combined with the sand, it enough to block the flow of food into her stomach and slowly starve her. We had finally found the reason why she wasn’t gaining weight.

Laysan Albatross chick before (left) and after a successful endoscopy with the veterinary team at VCA Specialty Clinic in Pearl City, Hawaii

Small piece of plastic inside the digestive tract of a Laysan Albatross

In the weeks and months that followed, number 9 struggled to catch up to her peers in weight and size, much in the same way a premature baby would. For most of the translocation season she was half the size of other birds the same age, but starting in June she began to rapidly catch up. Interestingly (and endearingly) she was our only chick that clearly liked being around humans. Maybe it was because she spent so much time with us as a young chick as opposed to with other albatrosses, or maybe she somehow knew that we had helped her. It’s hard to say, but she would often ‘talk’ to us as we walked by and look at us expectantly as opposed to her peers who would waddle away from us as we approached. Thankfully, she didn’t lag behind for long and by the time #9 fledged, she was just like any of the other translocated chicks, but with an amazing story.

Number nine days before fledging

While many have asked whether it was worth it to invest so much into one chick, our answer is yes. Yes because she is part of cohort of birds who will ultimately found a new population that will be important to the future of her species. Yes because what we learned from her was new to science, and yes because what we learned will help us immensely in helping to diagnose gastrointestinal issues in future translocated chicks. So for birds that are part of a translocation project, investing in resolving and learning from their medical issues will help us and others in the future successfully conduct these types of projects.

What has been interesting about this journey for us is how difficult it was to diagnose the plastic obstruction in an albatross chick, even with the most advanced modern medical imaging available. All we had to go on was a gut feeling and her weight. Unfortunately none of these are things that could be used in the field for wild birds, so for now we are still limited in our ability to diagnose plastic blockages in wild Albatrosses. But the good news is that even though plastic ingestion is a problem for wild albatrosses, the extent of the problem is likely not as bad as we think. Adult survival and reproductive success is virtually identical today to what it was in the 1960’s before the widespread use of plastic and before the existence of the floating garbage patches in our oceans. While plastic certainly isn’t good for them, and harms individuals (such as #9), it doesn’t seem to be having large population level impacts that we have been able to detect. This is likely because albatrosses regularly eat large undigestible items as part of their natural diet. We’ve found squid beaks close to an inch long, and pieces of pumice more than two inches in diameter. They are adapted to coughing up these large hard items which is why they have boluses in the first place. But research is needed to determine the secondary effects of plastic, such as the leaching of contaminants into their blood stream, and other physiological impacts that we may not know about yet. The story is complex. But regardless of whether they can deal with plastic ingestion or not, we hope that the tale of #9 serves as a cautionary note that we can all take measures to reduce our individual levels of plastic use- a birds life may depend on it.

The James Campbell Laysan Albatross translocation is the result of a partnership between Pacific Rim Conservation, The US Navy, The US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) and the Hawaii Department of Land and natural Resources. Funding has been provided by the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, the USFWS, the David and Lucile Packard Foundation and the American Bird Conservancy. For more information on the project, please visit:

https://pacificrimconservation.org/our-work/management/bird-translocations/